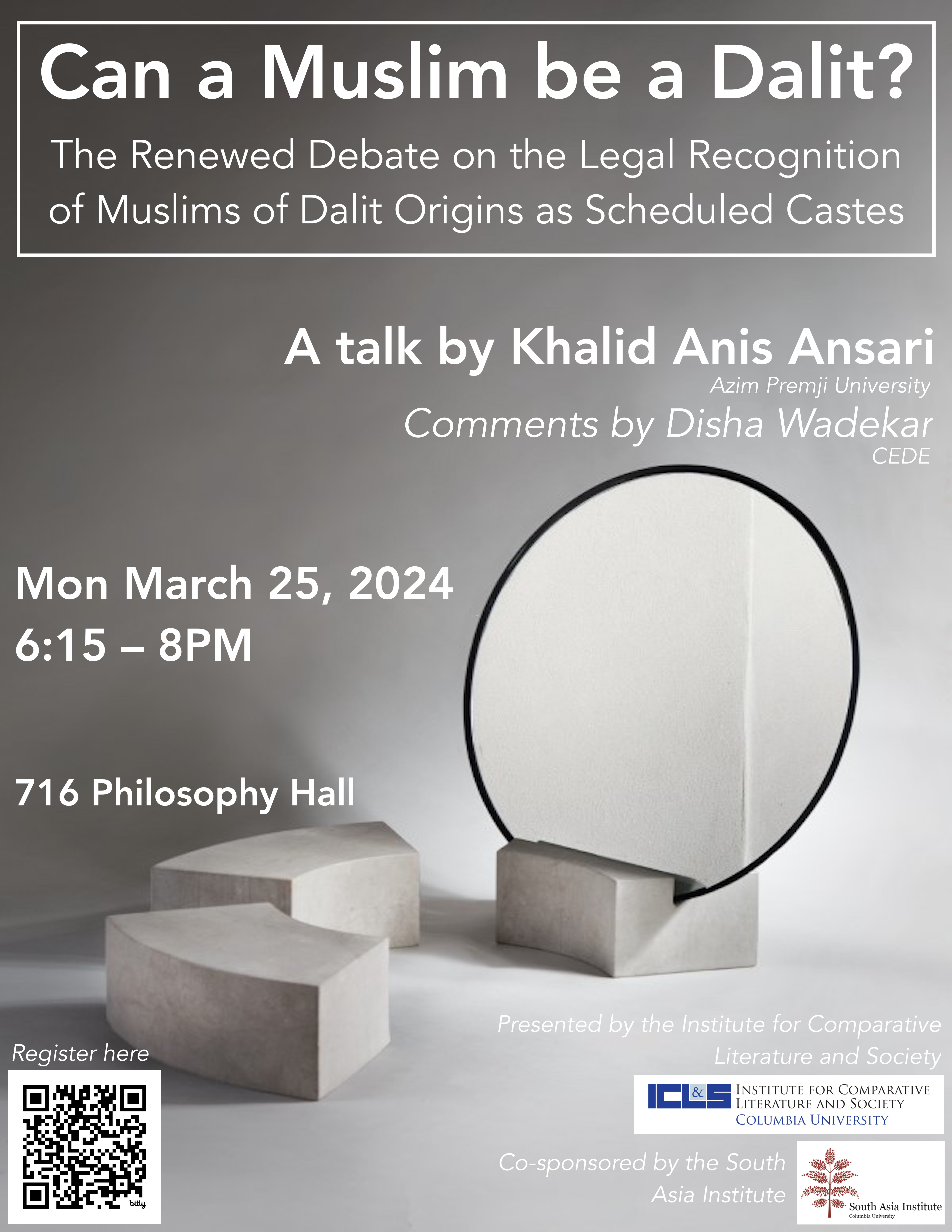

716 Philosophy Hall

Ambedkar Initiative at ICLS

Department of Philosophy, South Asia Institute

Can a Muslim be a Dalit? The Renewed Debate on the Legal Recognition of Muslims of Dalit Origins as Scheduled Castes

This event is part of the Ambedkar Initiative at ICLS.

Registration for this event is required. To register, visit the link here.

A talk by Professor Khalid Ansari. Khalid Anis Ansari is an Associate Professor of Sociology in the School of Arts and Sciences at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru (India). Comment by Disha Wadekar, independent advocate practicing in the Supreme Court of India, and co-founder and President of CEDE, an organization working towards a diverse and inclusive legal profession and judiciary.

In terms of the affirmative action matrix in India, while the Other Backward Classes (OBC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) categories are religion-neutral, the Scheduled Castes (SC) category is not. After the promulgation of the Constitution of India, the President, under Article 341 (1), issued the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order 1950, listing the “castes, races, tribes” to be included in the SC category. Para 3 of the order excluded all non-Hindu groups (with the proviso of four Sikh castes: the Ramdasi, Kabirpanthi, Mazhabi, and Sikligar of the Punjab region). Subsequently, the SC net was expanded through amendments, and the remaining Sikh and all Buddhist castes of Dalit origins were included in the SC list in 1956 and 1990, respectively.

The Muslims and Christians of Dalit origins have long struggled to lift the religious ban to be duly included in the SC category. Since 2004, several petitions have been filed in the Supreme Court by Dalit Muslims and Dalit Christians seeking the scrapping of Para 3, which is seen as arbitrary and unconstitutional. It violates Articles 14 (equality), 15 (non-discrimination), 16 (non-discrimination in employment), and 25 (freedom of conscience) of the Constitution. Recently, the Supreme Court decided to adjudicate the matter pending in the courts for over two decades, resulting in polarised conversations, particularly the opposition by a few significant anti-caste practitioners.

The opposition by anti-caste voices to the demand for inclusion of Dalit Muslims (and Christians) in the SC category militates against the aspirational pan-religious solidarity of lowered castes/classes advocated by the Bahujan/Pasmanda movement. While this opposition can be pragmatically explained as the elite capture of subaltern movements or the preservation of parochial caste-based interests by certain sections of aspirational Dalit castes, I argue that the debate must be fundamentally traced to the foundational orientalist-colonial closures of anti-caste thought per se—particularly the background orthodox assumptions on the relation between faith and caste, indigeneity, religious conversions, political minorities and so on. Rather than being interpreted as a setback, the recent disruptive provocations around recognition may be construed as an opportunity to confront the aporias of anti-caste thought and push us to reconfigure the grammar of democratic politics itself.

Please email disability@columbia.edu to request disability accommodations. Advance notice is necessary to arrange for some accessibility needs.